The new Child Poverty Strategy: objectives, impact and what it means for councils

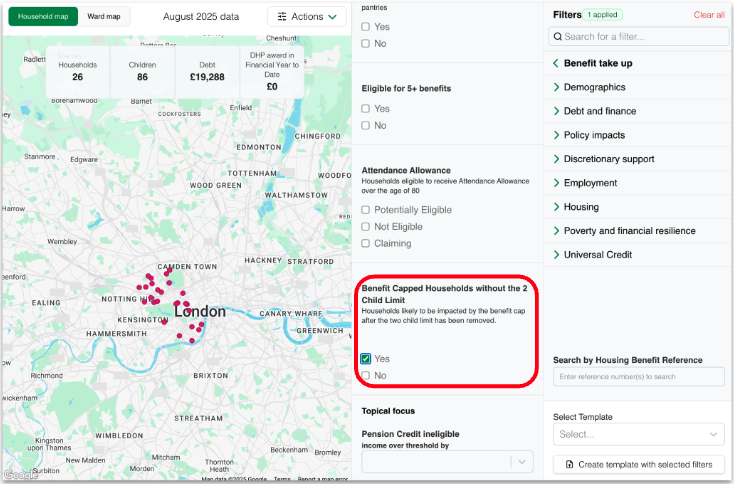

Policy in Practice is pleased to have contributed to the government’s Child Poverty Strategy. We particularly welcome the decision to end the two child limit and the strong recognition of the central role that local authorities will play in delivering the strategy.

In this blog we explore the objectives and likely impact of the new policies and show how our tools can help councils deliver on the new requirements.

The strategy, Our Children, Our Future: Tackling Child Poverty, represents one of the most comprehensive attempts in recent years to address the scale and persistence of child poverty in the UK. Although much of it brings together previously announced measures, and is somewhat curtailed by fiscal pressures, it also sets a clearer direction, introduces significant reforms and places new expectations on local authorities and public services.

At its core, the strategy recognises that child poverty is a structural issue shaped by income, housing, employment, public services and the cost of living.

The government’s objectives reflect this broader framing as it sets out to:

- reduce the number of children in poverty, particularly those in deep and persistent poverty;

- ensure that work provides a genuine route out of hardship;

- reduce essential household costs; and

- strengthen early help and public services so that issues linked to poverty are identified and addressed earlier.

Oversight will be provided by a new cross-departmental board, signalling an intention to embed responsibility for tackling child poverty across government rather than within a single department.

Why we need a strategy to tackle child poverty

The new child poverty strategy makes clear why an integrated approach is necessary.

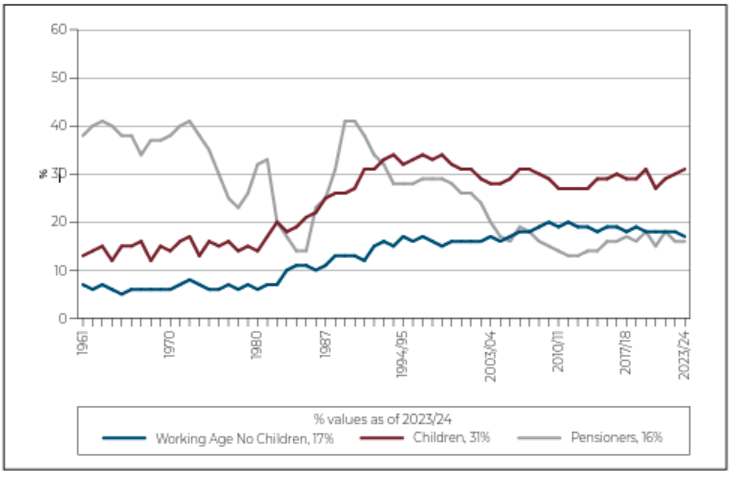

Child poverty is no longer closely tied to worklessness: three quarters of children in poverty now live in households where at least one parent works, and parents are more likely to be in employment than adults without dependent children.

Employment rates have risen steadily since 2011, yet poverty has not fallen, as earnings and social security support have not kept pace with rising living costs.

Support for the poorest families has eroded significantly over the past decade. By 2023/24, the average value of social security support for children in the lowest income quintile was £64 per week lower than in 2010/11.

Over the same period, household costs for low income families with children rose sharply, more than 30% higher by 2025 compared with 2020, while the Universal Credit standard allowance increased by only 6%. Food and energy prices rose even faster, and these pressures have contributed directly to rising housing insecurity.

By June 2025, more than 172,000 children in England were living in temporary accommodation, more than double the figure in 2010.

Relative low income (AHC) rate by age group 1960 to 2023/24 in Great Britain (Source: Our Children, Our Future: tackling Child Poverty, UK Government 2025)

Introducing a new poverty metric

The strategy also recognises the need for a consistent and credible approach to measuring poverty, an issue that has long challenged researchers, as every existing metric has its strengths and limitations.

By committing to two core measures over the full ten year course of the strategy, the government enables clear, year on year tracking of progress towards its aims and acknowledges that poverty is not only about income, but also about whether households can meet their basic needs.

The two metrics are:

- Relative low income after housing costs (AHC)

- Deep material poverty: a new measure based on a “material deprivation” test in which families are asked whether they can afford 13 essential items such as adequate heating, food, clothing and safe housing. Children are classified as living in deep material poverty if their household is unable to afford four or more of these items for financial reasons

The key measures in the Child Poverty Strategy

The strategy is broad in scope, covering policy areas including health, education, welfare, transport, housing and employment. The key measures are summarised below.

1. Removal of the two child limit

The most significant reform in the strategy is the commitment to abolish the two child limit in Universal Credit and Child Tax Credit.

The government estimates that this change will lift around 450,000 children out of poverty and reduce deep poverty for a further 700,000. This is a major shift in welfare policy and underpins a large share of the strategy’s projected impact.

However, the freeze on the benefit cap limits the potential benefits of this reform.

Recent research by Policy in Practice shows how the two policies interact, and that raising the benefit cap would have lifted even more children out of poverty. The absence of any reference to this interaction suggests that the government intends to maintain the current cap throughout the lifetime of the strategy.

2. Employment support

The strategy continues to emphasise employment as a route out of poverty, while acknowledging that employment support must better reflect parents’ circumstances.

All areas of England will be expected to develop local “Get Britain Working” plans, identifying local labour-market barriers and setting out how councils, Jobcentres and partners will work together to address them.

Jobcentres will adopt a more tailored approach for parents, taking into account childcare availability, health conditions and caring responsibilities.

3. Reducing a family’s costs

Reducing essential household costs forms the second major pillar of the strategy. Key measures include:

- Expansion of childcare support, including extending UC childcare support beyond two children and shifting to upfront payments rather than reimbursement

- Free breakfast clubs in all primary schools

- A three year extension of the Holiday Activities and Food Programme

From September 2026, free school meals for all children in households receiving Universal Credit, including those in nurseries, sixth forms and Further Education colleges.

New limits on branded school uniform requirements and stronger protections for children whose families struggle to meet uniform rules.

The strategy also addresses utility costs. The government commits to exploring more effective ways of matching and sharing data so that support can be better targeted to low income and vulnerable consumers. It is also reviewing the WaterSure social tariff and consulting on improvements to targeting the Warm Home Discount.

4. Housing

Housing pressures, particularly the rapid rise in temporary accommodation, receive sustained attention. While many measures restate existing policy, the strategy commits to:

- ending the unlawful use of bed and breakfast accommodation for families

- reducing reliance on emergency accommodation through targeted pilots

- improving health data through a new clinical code for children in temporary accommodation and

- implementing a new notification system to ensure schools are informed when children are placed in temporary accommodation, supporting safeguarding and educational continuity

On the last point, Policy in Practice’s LIFT and MAST products can work together to notify partners when children are placed in temporary accommodation and, as such, offer a valuable technical solution to local authorities and safeguarding partners.

The role of local government

Local government is placed at the centre of the delivery of the strategy. Councils are recognised as critical to tackling child poverty through housing, education, local welfare, council tax support and family services.

A new Local Government Outcomes Framework will set priority outcomes, many specifically linked to child poverty and wellbeing. Consultation has concluded, with the final framework expected this month, taking effect from April 2026. A digital tracking tool is expected in summer 2026.

Public authorities will also be required to actively consider socio-economic disadvantage in strategic decision making, embedding poverty reduction into mainstream policy and service design. This will be supported by a new Children, Families and Youth Grant within the Local Government Finance Settlement, and improved data sharing to support better targeting.

Within this wider framework, council tax is identified as an important but often overlooked lever.

The government is considering the impact of collection and enforcement practices on vulnerable households and will issue non-statutory guidance outlining its expectations and examples of best practice. It is also reviewing how local council tax reduction schemes interact with the wider benefits system, recognising that misalignment can undermine national policy goals.

Statutory guidance will encourage councils to consider the circumstances of vulnerable families when designing their council tax support schemes.

Taken together, these commitments reflect a shift towards viewing council tax policy not only as a revenue tool but as a mechanism that shapes child poverty and financial resilience

Will the strategy be successful?

Overall, the Child Poverty Strategy marks a more coherent and joined up approach than has been seen for some time. The decision to abolish the two child limit represents a significant policy shift. However, success will depend on sustained funding, effective local delivery and the degree to which national ambitions translate into real improvements in children’s lives.

Although the strategy recognises child poverty as a structural issue affecting almost every area of public services, it stops short of requiring all government departments to assess the child poverty impact of their policies, unlike the approach taken in Wales.

As a result, policies such as the freezing of tax thresholds, the freezing of LHA rates, and the retention of the frozen benefit cap, all of which contribute to rising poverty, remain unaddressed. Proposed reforms to disability benefits may also work against the strategy’s aims.

Another potential weakness is the government’s reluctance to legislate for change, relying instead on shared objectives and voluntary practice. For example, Policy in Practice’s research for the Welsh Government shows that voluntary codes of practice on council tax collection are often inconsistently applied. Without legally enforceable commitments, there’s a risk that promises may not translate into sustained action.

While much of the child poverty strategy reflects already announced initiatives, the commitment to measurable outcomes, illustrated by ending the two child limit, indicates that the government intends to pursue its objectives in partnership with local government and the third sector.

This is underlined by the commitment of the government to monitoring and evaluation of outcomes. This is set out in a high level monitoring and evaluation framework, which outlines whether the strategy is on track.

How Policy in Practice can help councils meet the objectives of the Child Poverty Strategy

Policy in Practice has been working with councils to tackle poverty and target resources to those most in need for over a decade. The importance of this approach is evidenced within the Child Poverty Strategy, particularly the use of data to more effectively target support.

Some specific areas where we can support councils in meeting the strategy’s objectives are:

- LIFT: Identifying children who won’t benefit fully from the lifting of the two child limit, because of the Benefit Cap

- LIFT and MAST: Notifying partners, including GPs and schools, when a child is in temporary accommodation, something local authorities struggle with particularly when children are placed out of borough

- LIFT: Providing a single view of debt, supporting income maximisation and ensuring that vulnerability and poverty are visible

- MAST: Introducing a multi-agency approach to understanding vulnerability

- Policy modelling: Support with designing local council tax reduction schemes to ensure these take account of the impact on households and align with the forthcoming statutory guidance

Next steps

- Register for our free webinar on CRF: Resetting local crisis support in England. Wed 21 January

- Read our case study: Lambeth Council tackles child poverty by auto enrolling 1,500 students in Free School Meals

- Contact us to for a behind-the-scenes tour of our Better Off Platform